What Caused the Collapse of the Nova Kakhovka Dam?

Part 4: How the Dam Was Undermined

July 25, 2023

Bombs vs. Erosion and the "Paper of Record"

Part 2 in this series covered the hydrologic overload that kept the reservoir of Lake Kakhovka 99-100% full for one month despite intense, non-stop outflow from 4 floodgates. Part 3 considered why those same 4 floodgates stayed open for 6 months straight, narrowing the heavy flow. That's still a mystery, but I suspect Ukraine turned off the power source, located on their bank of the river, for the gantry cranes needed to open and close the gates. As I'll explain here, that constant, heavy, and narrow outflow seems likely to have fatally undermined the dam with erosion by early June. I can't rule out that explosives were used to destroy the dam, but if so, it came with the coincidence that it was likely to come very down soon anyways.

We'll start with a widely-cited New York Times article from ten days after the collapse that found for explosives over erosion, but in a very unsatisfying way. Their evidence, in summary: the seismic record suggests a blast, or rather the two blasts their story needs (debatable), US satellites were said to pick up "infrared heat signals that also indicated an explosion" - one of the 2 required (no details like exact time, degree, or location), and how from the deep central flow after collapse, it seemed like "the foundation had suffered structural damage" that couldn't be caused by any piddling rocket impact to the top, which might have made this partly Ukraine's fault.

By this, a bomb seems possible but far from proven. It could be done by either side if so, especially considering motive. But the writers skip this, and overlook the abnormal flooding and other clues to conclude the dam was doing well enough until the side with better access but unclear motive - the Russians - must have bombed it from the inside. That was another big clue for the Times: the Russians could do it from the inside, totally unseen by drones or satellites. That's eerily true! They could have ....

The report points out that "the catastrophic failure of its underlying concrete foundation was very unlikely to occur on its own." It suggests the Russian bomb(s) were set in the "drainage gallery," a tunnel at the dam's "base" that ran to both sides of the river, but was guarded by Russia and presumably blocked to Ukraine. It turns out the Times' graphic moves the tunnel well towards the bottom of the dam, compared to the blueprint design I've seen, and makes it bigger. Here are the 2 views overlaid with notes added. A blast just below the floodgates would still be a serious issue for the upper structure, and might explain the observed flow, but it's far less likely to effect the deep foundation than their graphic implied.The dam runs SE to NW (right to left here), 2/3 filled with 28 basic floodgates numbered right-to-left, done in red. Note that gates 3, 5,6 and 7 are raised, or open, as they were all through 2023. Gate 12 is actually red, somehow taller, or open but with another gate blocking the flow - it's effectively closed. Gate 1 and gates 26-28 at the far ends were closed but leaking from damage caused by both sides. Blue gantry cranes that open the gates are numbered the other way around and here are the south & north cranes, parked for months over gates 3 and 8. South/right end is the hydropower plant, its own 6 floodgates gates, and its own gantry crane (hidden behind in this view). The dam and HPP each have a water "outlet" running, as shown, to 100m from the water ramps, with a divider between the outlets. Most of this is atop the concrete "apron" or basin about 3m thick, with the inner part of the dam outlet covered in 4 meters of concrete. This model shows the entire apron/basin. I'm not certain just what kind of bottom there was past this.

And here's a short review of explosives at the dam. Some were fired in rockets by Ukraine, or some say by the Russians, from early August to early November, causing widespread but non-fatal damage near the HPP and floodgates 1-5. Then it seems Russians had blown part of the roadway off the top of the dam after they retreated last November (over gates 26-28), then "mined" it and/or planted explosives-filled cars on the remaining stretch, all to keep Ukrainian forces off the bridge. Those car bombs never detonated. One of the mines might have gone off during the collapse, injuring a seagull. None of it caused the collapse.

Kyiv also accuses the Russians of importing explosives into the dam's interior. By reports from dam employees, including to OSINTJOURNO, the Russians had blocked or "blew up" the north entrances to the drainage gallery to keep Ukrainians out. ("The Russians were concerned that the Ukrainians would misuse the drainage gallery of the dam" tweet.) Then they reportedly mined it with explosives - likely smaller anti-personnel ones, in case anyone managed to break in. ("In March, the Russians already blew up the entrance from the northern side, and since then, they have completely undermined the drainage gallery by placing explosives at various locations in the "drainage holes" and "curtain grout holes"." tweet) This isn't a certain fact, but it's likely enough. These "grout hole" bombs might be triggered by tripwires or motion sensors, or may be triggered accidentally by an unexpected event, like the dam starting to collapse on its own.

Bombs alone, as the Times proposes, would require 2 bombs or 2 phases. There was an initial blast and/or collapse at 2:35 am, after which the span from gates 1-9 were seen missing, and then a middle section of the HPP engine room also collapsed 20 minutes later, with a seismic reading that looks the most like explosives. As first published, with my labels, this may show a blast for 2 seconds, or perhaps several smaller ones. Then it shows 20 seconds of the dam collapsing, with cracks even louder than that possible bomb(s) - all 20 minutes AFTER another section must have been bombed with a notably quieter blast (not shown here).

I don't know of any credible evidence for explosives in the HPP engine room, aside from its collapsing separately, and apparently with the louder signal shown above. But it's possible. Otherwise, the mined drainage gallery ran under the place, or maybe just up to it, with a direct doorway connection. NYT: the gallery is "reachable from the dam's machine room," and vice-versa. So for what it's worth, any Ukrainians who got into the tunnel without being blown up might be able to access the engine room as well. Some delayed blasts there or in the tunnel below, coming amid a partial collapse, could set that whole section floating down the river.

But then again, this might be a natural second phase of an ongoing collapse, with cracks that come on suddenly and read almost like a bomb blast.

Mining the drainage gallery sounds reckless, but the explosions might be small and non-fatal to the dam under normal circumstances. A collapse would be abnormal circumstances and there were more of these in the months leading up to it. It seems there was heavy erosion of a kind the Times' experts apparently didn't know about. They considered it an unlikely possibility when, as I'll show, it's closer to a visually proven reality. Gregory B. Baecher, an engineering professor at the University of Maryland "said it was possible, though unlikely, that water flow from the damaged gates somehow undermined the concrete structure where it sat on the riverbed." But he noted design features we'll consider below, including "a so-called “apron” of concrete on top of the riverbed to the downstream side of the dam," that would make this unlikely. This is exactly the right first impression to get, but there are second impressions in order here.

The article - if not their experts - did take note of some important evidence in this regard; "On April 23, a small part of a wall connected to the power plant collapsed — possible evidence of erosion near the dam." It's virtual proof of erosion, and it would happen under this same concrete apron. And if the same erosion somehow expanded in May and June, say under extreme water pressure, it might claim a big section of roadway they also noted collapsing, presumably from damage it had suffered in attacks:

"On June 1, or early on June 2, part of the road that runs along the dam collapsed. Ukrainian HIMARS rocket strikes in August 2022 damaged that part of the road but did not hit the dam."

Here are the best views of this (from Maxar) from May 28 and June 5. In between these views, sometime between other images of June 1 & 2 as it turns out, the rocket-perforated section of roadway vanished, along with two massive support columns that held it, and 2 attached flow guides around floodgates 2 and 3. Dated graphic: "dislodged since March" is what NYT meant was dislodged on April 23, and "since 5/28" is what vanished on June 1/2. In the left view, note the flow guides marked with green curves, and how those are unevenly spaced - one that would collapse is already visibly slanting to the right by May 28.

As suggested in my part 2, and as I'll expand on in part 5, the water overload that contributed to this erosion can only have been caused by Ukraine and its hydropower agency Ukrhydroenergo, who controlled five reservoirs on the Dnieper feeding into Lake Kakhovka. These wound up at about normal levels in June, shedding heavy April rainfall and some of what they had before, at the same time Kakhovka was swollen to a disastrous level and kept there until the dam collapsed. The overload, injected directly by the various floodgates of the Dnipro HPP at Zaporizhzhia, was never lessened even as signs of impending disaster grew thicker in April, May, and early June. I'll address that some more in part 5.

Especially with the mysterious cranes/floodgates issue and other complications resulting from "disputed" shelling attacks over the fall, this looks like a deliberate plot, using the river as a weapon of mass destruction against the Russian invaders. While I can't rule out a Russian bomb plot, there's little logic to it. And why would both sides have plots to destroy the dam culminating at the same time? If there was a bomb plot, it would probably be Ukrainian and coordinated with their flooding plot. Why? Maybe just to have explosions seen, assumed as the cause, and used to blame the other side.

Others on Twitter had secured designs and historical photos to show a concrete apron or basin over the riverbed for a long span. Below is cropped from a profile view blueprint, view via Kos Palchyk 🇺🇦 on Twitter, noting label 4 translates "arpon," marked 4,0 = 4 meters thick.

The water ramps in the dam are shown at their true scale, starting 21m above the river bed at "0,0". Right is downstream, with the concrete apron beginning immediately below the foot of the ramps (right of center). It is definitely a separate construction, with a gap between shown with a line running down well below the concrete - leakage was expected, and it would drain into the aquifer below. The concrete cover runs for 100m downstream, most of it thinner, with the 4m thick span running about 40m of that.

For my fellow US citizens, 4 meters = about 13 feet. That's pretty thick. It might be thinner in the final reality, but we should assume this is accurate. Here's a construction photo where workers climb close to 2 meters up some stairs up to the ramps. The concrete those stairs rest on is probably more than twice that thick.As I reason it out, excavation of the subsoil would require cracks to the bottom that allow water to flow in all the way to mobile soil, and then back out, carrying some of it. Some soil has to be dislodged and floated away before any room is made for more water and more erosion. Once that's started, this can keep washing out more sediment, undermining more concrete. I reason this could spread in both directions, but especially in the downstream direction. But getting started shouldn't be easy, unless that very thick concrete were somehow broken up, making more seams all over, irregularities where new low points attract flowing water, perhaps clear to the sediment below, and gaps allow it to flow away - more erosion points, undermining concrete chunks, letting them settle lower, exposing new areas for more of the same.

Side-note: in the construction photo above and others, we can see the concrete of the ramps and the dam at large is steel-reinforced, with some visible ends of reinforcing bars. This will form a loose mesh within the concrete, helping it hold together even if it's damaged and eroding. The basin likely is the same, but perhaps not. It probably doesn't matter a lot either way; if it's broken enough to let erosion start, the rebar just holds together at first, when big pieces are still jammed against each other in the loose rebar cage. Once the first few "birds" fly from that cage, the rest will fly out, and then flock out, easily enough.

Pre-Existing Erosion & Sinkage?

Natural processes have had a long time to operate on the dam since it was built in the 1950s. OSINTJOURNO has photos showing the effects of settling. A good example is here just west of the dam's north end (Google Maps 2015 street view), where the land slid tens of centimeters, leaving a gap and a badly misaligned edge. The dam itself probably settled here, pulling the attached concrete over. It seems this happened some time ago and was long-since fixed with metal plates bolted over the gap (though it seems a plate went missing for this view), and with a "bent" railing made to fit the new edge. As I gather, the many rusty padlocks on the railing are (kind of expensive) mementos people leave there for some odd reason. This spot seems to have a special appeal for lock-leaving. https://twitter.com/osintjourno/status/1672896260162961408

This kind of settling, possibly caused by subsurface erosion, is a general issue that could happen in different spots, especially with heavy structures and earthen constructions weighing down. Invisible shifting of the basin under the water has only the river and the concrete's own weight bearing down. But considering the often rapid flow downstream, once anything managed to start, it could easily accelerate. And there has been a long time for both things to happen.

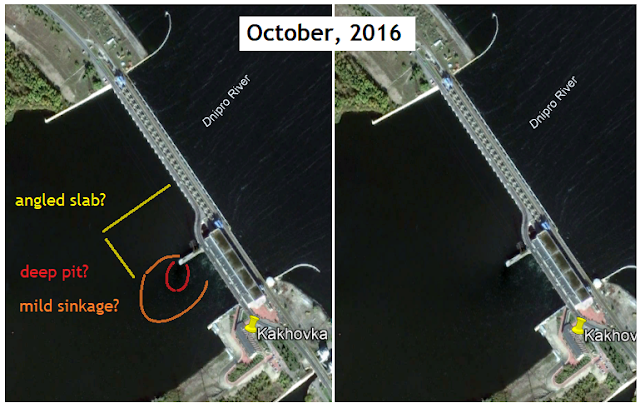

A Pit? Another, far more relevant spot near the opposite shore might have a fairly large sinkhole that was visible at least once. This is at the end of the divider (or "flow guide" or "training wall") between the outputs of the dam and the HPP. Google Earth historical view of October, 2016 shows what looks like a dark ovular pit there, oriented north-south. It looks like a river bed faintly lit with sun from the south, where the light suddenly falls off drastically (red oval). This could just be just an illusion, but it's not a regular shadow of any visible object, and it doesn't look like a cloud shadow. A wider area around it (orange) appears slightly sunken, by the same visual reasoning, and includes a possible increasing gap or depression all along the divider. This is mainly in the HPP outlet, where the concrete is slightly thinner and more vulnerable. GE 6/2021 might show the same dark oval beneath the waves.The photo above was taken April, 2008. (Вид на Казацкое - Google Maps). This issue may go back a while.

Chris Kabusk noticed a matching but inverted pattern at the same spot on the opposite side of the divider (right) - a light stripe of, I think, chipped away concrete, with a mild angle to it low on the second block down. I'm not sure what date this was taken, but other views show this same pattern, including the Google Maps street view from July 2015.

As I'll show below, heavier flows in 2023 would consistently swerve towards the possible pit, perhaps with the assistance of some new erosion, and/or as the pit likely grew under the year's constant overflow. And it's this spot that witnesses the first visible subsidence of dam structures in 2023, when the tip of that divider broke off and settled at an angle. This happened April 23, per NYT's report. The earliest clear view I know of, from April 28, shows its broken end askew at upper right. (Каховська ГЕС, скидання дніпровської води може призвести до катастрофи - YouTube). By the basic length vs. width of the broken chunk, the wall probably broke along the same line it was already cracking at.

And on the reservoir side, he spots a possibly different slant to supports between gates 2 and 3 (right).

Any such thing as a existing pit, an undermined and slanted apron slab, or a fracture and settling of the main structure at gate 3, was quite likely known to Kyiv and its war planners. They might even find a way to take advantage of such a weak spot, if they had any plans that fitted into.

Rockets in the Riverbed?

As noted, Ukrainian rocket attacks of August and November are unlikely to have caused significant damage to the dam itself. The strikes we know of, that we've seen images of, were to the floodgate 1, the structure around gates 1 and 3, and mainly to the road surface and rails, and the tops of the supports beneath the roadway. Other impacts to the structure, including parts underwater, are quite possible. But if so, and whatever the actual damage was, it's the kind that only gives way 7 months later once other things have changed, so the following points apply.

These spots would experience direct damage and wider shockwaves, likely forming small cracks that contributed to the failure ONCE the whole structure was compromised enough to start giving way at these cracks. If it were partly undermined by erosion and sagging over that, as well as forward/downstream under maximum water weight, then somewhere around the middle of the undermined area, a fatal strain could form, seeking out available cracks and pulling them wider. Otherwise, it would probably hold for quite a while, if not forever.

But consider that that the dam is a fairly narrow target for long-range rockets, even precision ones like those of the U.S.-supplied HIMARS system. It's easy to miss, in which case some rockets would land in the water, detonating on contact with whatever concrete it ran into. These would cause limited but real damage to the basin, or perhaps to the dam itself.

Basin damage on the upstream side could play into erosion, The constant outpour would pull it in more than usual for all of 2023, especially nearest the open gates, with the known attack spots near them. But still, erosion here doesn't seem as likely, or as likely to matter, as on the downstream side - it's basically a lake on one side and a river on the other. And it's downstream where we see real erosion that probably mattered greatly.

Above, I noted a possible slope to the downstream concrete apron between gates 1 and 9 - visible by 2016, suggested by 2008. This would likely have some flow under it as well, excavating to an unclear degree but over years. This could leave some sections unsupported by 2022/23, leaving them to sag under their own and the river's weight, and start to crack. When hit by explosive rockets, any such spot could crack worse and might finally give way, sinking perhaps more than 4 meters, creating new river access to subsoil, new pits and troughs to even better channel the flow to this side.

Rocket strikes in August (gold arcs) and/or November (red arcs) might include unseen hits to the concrete apron under the downstream flow, beginning or worsening erosion there, maybe expanding the small gap between the apron and the dam's base, allowing erosion directly beneath the dam, undermining it as it remained 100% full, with immense and high-centered water weight.

this angle of fire slightly from the dam's left is just approximate, from one estimate of mine - the real angle(s) will likely vary, and depending on that, the upstream side (left) of the dam itself could easily be hit as well, and possibly the downstream side. But if so, again, it's the kind of damage that only gives way 7 months later once other things have changed.

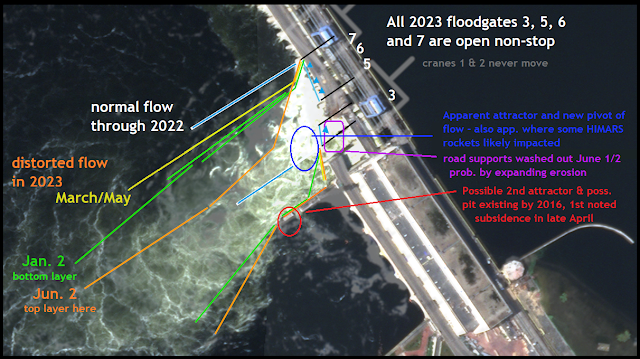

Increasing Erosion, A Re-Shaped River

So there was a likely old pit and angled slab, probable new damage, then months of erosion under heavy and abnormally concentrated flow from adjacent floodgates 5, 6, and 7, besides from gate 3 and an irregular partial flow from gate 1 - new erosion in that light ...

Gate 1's irregular flow - could add to the relevant erosion - Normally water is released with an even, uniform flow across its width - here it's 2 spraying streams from the sides, with more from the right side as seen, spraying to the left. That will cause 2 flows, the greater one on the left, closest to or in front of gate 2's outflow - and greater erosion potential where the streams cross. If this were just soil, I could see a pit forming along that edge. If it has to leak down below an intact concrete slab, perhaps into an already sunken channel at the base of the angled slab, it shouldn't matter. But if the slab is broken enough to allow serious gaps, then erosion below is possible.

Gate 3-7 flow - April 28 video:

Normal turbulence can look about this intense and extend even further over what should be smooth concrete. But it seems to me this usually happens in bigger, smoother waves of a kind that only appear at the far edges here. In the center, the foamy ripples seem smaller and more violent than usual. This might reflect a broken basin with sharp edges the water splashes against, for a whitewater rapids effect. If so, that would be a sign the dam was in major trouble, and Ukrainian drones were seeing it this early, as the was just reaching the maximum safe level of 16.5 meters. And yet, Kyiv's wartime dam operators continued to flood the reservoir over the next 5-6 weeks.

This flow was well off from perpendicular (black lines marking flow from gates 3-7). Note the elongated area to and past the flow guide, angling towards the shore. This is probably a sunken trough, or at least includes significant lower spots. The flow from gate 7 seems just faintly distorted, but the outflow from gates 3 and 5 must be seriously off track to fill that whole corner so fully with froth.

This angled flow is a big clue. A February NPR report includes a January 2 satellite view showing the basic final flow held through May, with the pull less clear on the distant north edge but all starting with a sharp swerve south, towards that divider. This is shown in the green and yellow lines below. Water pouring across the possible "angled slab" would angle evenly across its width until it splashes into deeper water. Here it may start with this, with gate 3 outflow quite distorted, 5 less so, and the pull on gates 6 and 7 outflow was still muted through May.

In time, by June 5, the entire flow across the surface is swerving intensely to the south, as shown in orange. It seems the sharpest bend is towards the blue oval here. Maybe expanded erosion led to a steepened incline of the slab, or further damage-related settling, say from rocket hits near gate 5, has formed an outright trough along this stretch. All this water churning down into whatever spaces were formed would let out more and more support from beneath the dam. By this point, a solid pit is likely from at least gate 3 to the divider wall and its pit, and to that purple area at least.Here's another view from below. Plant growth in that crack suggests this too became somewhat undermined years ago, but it only gave once a lot of other things changed really fast in 2022-23.

Finally, the effect of the June 1/2 road collapse is likely to matter a lot. To the extent anything really fell, it's into the same basin. This would cause new cracks probably worse than any before, in the crucial span between the dam and that likely pit in the blue oval area. This might cause continuous damage to the existing pit (red oval). By then, if not already, there would be a continuous and massive swathe of damaged concrete and riverbed subject to widespread erosion, as 4 gates' worth of maximum pressure water kept pouring nonstop into that area for another 4 days. If nothing else in combination would have undermined the dam, this could well be the strawbale broke the camel's back.

From there, it wouldn't have to spread far to undermine the dam, and it probably spread faster in this last phase. Even after decades of settling and erosion, likely several HIMARS rocket impacts, abnormal wear of a constant, narrowed flow perhaps directed by an existing slope, it still took some 7 months before those final days where the process accelerated so terribly. That's a testament to the dam, in consolation for its callous destruction.

After the collapse, a re-shaped river still moves "down, as possible." July 3 Sentinelhub view and an earlier drone view show the river's central flow (white) with areas of prior erosion interest (blue: likeliest rocket impacts from August-November - purple: where curved roadway and supports collapsed June 1/2 - red: possible existing pit (by 2016) - pink: piece of the dam likely stuck in that pit.)

This is basically the same swerving flow as earlier in 2023 and seemingly related to these erosion points - pink at the far side of the expanded pit, and the other side probably extends back to the dam and under it, being the main reason for its collapse. As it was in April, the flow continues at an angle, almost to the shore. It didn't matter much for the dam, but the erosion must have spread a way downstream from the red oval, forming a trough shaped by the flow into the area.

The swerve became permanent. Some of its cause is old news, but it seems that US-supplied HIMARS rockets helped to reshape the Dnieper River, along the way tearing down the Nova Kakhovka dam and unleashing a catastrophic flood on tens of thousands.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

b.png)

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments welcome. Stay civil and on or near-topic. If you're at all stumped about how to comment, please see this post.